From Oliver Cromwell Case’s letter to his sister dated October 31, 1861 written at Camp Buckingham, Jamaica, Long Island, New York

This phrase caught my eye for the first time even though I’ve read this letter at least a dozen times. It caused me to go back and ponder some previous posts on this subject.

What sounds familiar about those words? It took a little research to pinpoint where I had heard a similar phase…

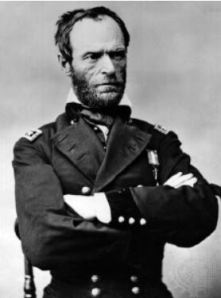

…from none other than William Tecumseh Sherman!

There is nothing too good for the soldiers who wear the blue.

Of course, Cump Sherman’s words came about two years after Oliver penned the phrase. Both understood the sentiment of the military leadership and the people of the north. However, Oliver’s declaration from Long Island came at a time when public support for the war effort remained high in the north, the Copperheads notwithstanding. With only about four months worth of significant combat action, the public had yet to grow wearily of the toll the war would soon begin to exact upon the lives of their young men. New Yorkers were among the most enthusiastic supporters of the boys in blue in the fall of 1861.

We are treated much better here than in Connecticut by the citizens. They think there is nothing to good for the soldiers. We are treated with respect wherever we go…[1]

However, after departing from Long Island on November 1, 1861, Oliver and comrades of the 8th Connecticut would find an even warmer reception awaiting them in the city of brotherly love. We pick up on Oliver’s retelling of the story from his letter of November 3rd:

We were got upon the cars with but little delay and tried to start for Philadelphia which was not so easy a job as you might imagine as we had on 19 passenger cars, but with the help of another engine we got under way and arrived safely at ½ after eleven o’clock where we had a huge dinner and if anyone ever did justice to a dinner, we did to that. I think I never tasted anything so good in my life. We stayed there until nearly five talking and shaking hands with everyone.

On November 2, 1861 from 11:30 in the morning until 5 o’clock in the afternoon, Private Oliver Cromwell Case and his fellow soldiers were hosted by the citizens of Philadelphia. My twenty-five years of service as an Army officer has taught me well that Soldiers with free time in a major population center can spell trouble if not properly occupied and supervised. Chief among the activities of these Soldiers is always the pursuit of food. In fact, when serving as a young lieutenant in the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment, I was told that one of the rules of the Cavalry Trooper was “never pass up the opportunity for a meal because you never know when you might eat next.” So it was with the nutmeggers on that November day. When Oliver writes that “we had a huge dinner” after arriving in Philadelphia, it’s likely that he had no idea that the keen observations of one of the city’s businessmen and the efforts of a group of ladies was to thank for that meal.

Only six months prior to the arrival of the 8th Connecticut, the citizens of the Philadelphia took action to support the growing number of troops transiting the city. During the closing week of April and the first week of May, Union regiments from the New England states began arriving by both ship and train. Most of these troops proceed along Washington Avenue to board trains bound for Perryville, Maryland, the southernmost location in Maryland accessible by railroad. After noticing the hundreds of soldiers sitting along the streets of the city waiting for their trains, a group of women in the city “formed themselves into a committee, and, with the assistance of their friends and neighbors, distributed coffee and refreshments among the hungry and grateful troops.”[2] These modest efforts to provide refreshments continued for several weeks until the last week of May 1861 when a Philadelphia businessman became involved.

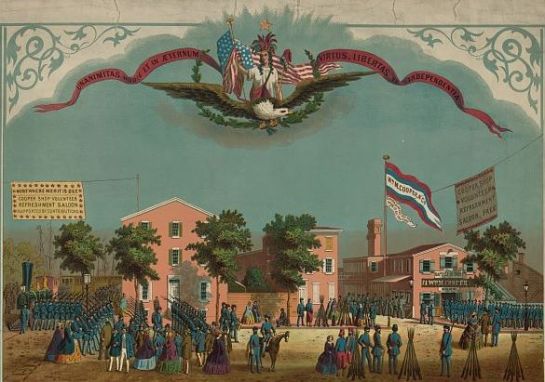

William M. Cooper was a merchant with a store located on Otsego Street just off Washington Avenue when he also noticed the large number of soldiers lounging on the streets of Philadelphia. He managed to convince his partner, Henry Pearce, that their barrel making business could be used to advance the mission to the soldiers started by the ladies of the city. As a result, on May 26, 1861, the Cooper Shop Volunteer Refreshment Saloon opened its doors to serve the Union soldiers passing through the city. Mr. Cooper took the lead role in the effort and served as the committee’s president and chief fundraiser for the duration of the war. A friendly rival, the Union Volunteer Refreshment Saloon, began operating nearby shortly after the establishment of Cooper’s saloon.

The two refreshment saloons provided a welcomed relief for the weary soldiers. As the ladies had first realized, a soldier’s first longing after the long boat or train ride was a cup of hot coffee and so Mr. Cooper converted the large fireplace in his shop into an enormous stove. With this setup, it was possible for the volunteers to brew one hundred gallons of coffee per hour! According to a history of the saloon written immediately following the war, the “coffee was made good and strong, and served up in a purely democratic manner.”[3] I would assume this means that it was one cup for each man.

Exterior view of the Cooper Shop Volunteer Refreshment Saloon (Library of Congress)

According to the records of the saloon, the soldiers of the 8th Connecticut were divided equally between the Union and Cooper saloons. Oliver does not indicate in which establishment he partook of the “huge dinner” but when he entered the building, he found:

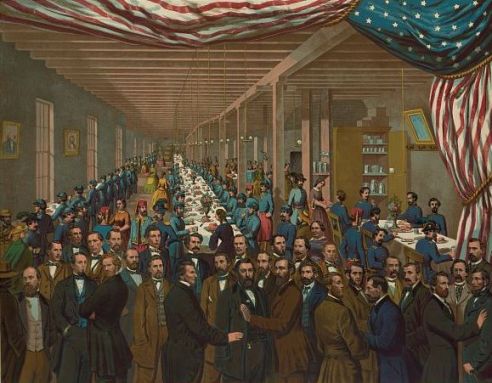

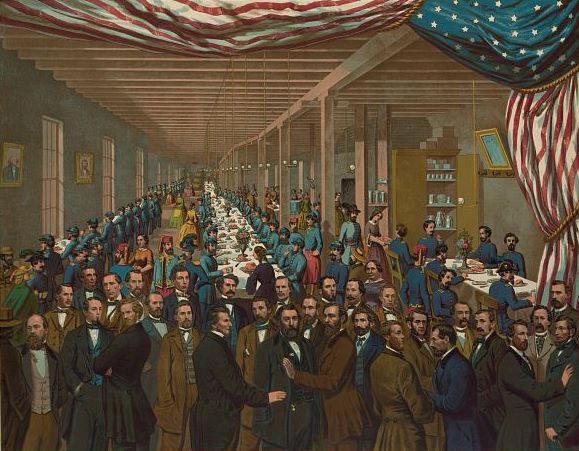

…each table was laid with a clean white linen cloth, on which were arranged plates of white stone china, mugs of the same, knives and forks, castors, and all that was necessary to table use. Bouquets of flowers, the gifts of visitors, were frequently added, and lent their fragrance to the savory odors. The bill of fare consisted of the best the market could supply, and was not, in the articles provided, inferior to that of any hotel in the country. At all meals the fare was abundant; consisting of ham, corned beef, Bologna sausage, bread made of the finest wheat, butter of the best quality, cheese, pepper-sauce beets, pickles, dried beef, coffee and tea, and vegetables.[4]

Interior view of the Cooper Shop Volunteer Refreshment Saloon (Library of Congress)

The Cooper and Union saloons provided an incredible setting for the soldiers to enjoy their meal. One Union Army surgeon provided a detailed description his experience at the Cooper saloon:

We are stopping over Sabbath in Philadelphia, at the above named saloon, where we have been treated with the kindest hospitality. We were met at the ferry by one of the committees, who conducted us to the saloon, where we found tables groaning beneath the real substantials of life. The hall is 150 feet long, by 30 wide, and will accommodate about 350 persons at a time. It is splendidly decorated with wreaths of evergreens, and a great variety of paintings and flags, and is well lighted with gas. At the further end of the hall is a large eagle, stuffed and perched upon a frame enclosing the Declaration of Independence. We were supplied with every thing we could possibly wish.[5]

In September of 1990, I found myself in much the same position as Oliver and the Connecticut boys…waiting around for transportation on my way to war. The USO with many volunteers had established a “saloon” at Rhein-Main Air Base in Frankfurt, Germany providing food, entertainment and, yes, coffee for soldiers deploying to Saudi Arabia in support of Operation Desert Shield. The facility was operated in a German “feast tent” just off the tarmac of the airbase. I don’t believe we enjoyed the same meal as Oliver, but the food was fantastic and represented the last taste of home for many months. Upon return to the United States after the conflict in 1991, we found the same reception waiting for us in both New York and our home base in El Paso, Texas. Today, a USO reception center is found in every major airport in the country and at United States military airbases around the world providing that same warm welcome and food (among many other services) that greeted Oliver Case and the soldiers of the 8th Connecticut in Philadelphia over 150 years ago.

The facility at Cooper expanded to include a hospital on the second floor of the building and both saloons hosted upwards of one million troops during the four years of the war. Mr. Cooper poured his heart, soul and finances into the venture. Sadly, in March of 1880, he died in a condition of debt so abysmal that friends and former soldiers assisted by the Cooper saloon had to come to his rescue to prevent his home from being sold at public auction. William Cooper was fondly remembered as the man who “used his private mean liberally, and no soldier was ever turned away hungry.”[6]

In addition to the History of the Cooper Shop Volunteer Refreshment Saloon by James Moore written in 1866, the following sites provided useful background information on this subject:

The House Divided site of Dickinson College Essay on Philadelphia

Civil War Philadelphia – Volunteer Refreshment Saloons

Notes:

[1] All quotes from Oliver Case taken from the Letters of Oliver Cromwell Case 1861-1862 (unpublished), Simsbury Historical Society, Simsbury, CT (October 31, 1861 and November 3, 1861) unless otherwise noted.

[2] History of the Cooper Shop Volunteer Refreshment Saloon, James Moore, James B. Rodgers, Philadelphia, 1866.

[3] Moore, 1866

[4] IBID

[5] IBID

[6] “A Patriot’s Family in Distress,” New York Times, March 18, 1880.