160 years ago, Private Oliver Cromwell Case stood shoulder to shoulder with his fellow soldiers on a hill outside Sharpsburg, Maryland fully prepared to die. What happened to Oliver in those final moments can only be known by the accounts of others. Here is an attempt to capture those last steps of Private Case on the battlefield of Antietam.

O death, where is thy sting? O grave, where is thy victory?[1]

The American Civil War connected death and dying to the country’s citizens like no other war before or since with an average of 600 men dying in the conflict every day. Per week, that’s more Americans killed than died on September 11, 2001 and the fact that this continued for four years is a difficult reality for most of us in modern America to firmly grasp. Two percent of the entire population of the United States (31 million in 1860) were killed, died of wounds or died of other non-combat causes during the war. Everyone, north and south, was touched by the death of a soldier or sailor either directly or indirectly.

Any Civil War soldier who had faced combat, understood that his death could be just over the next hill. Marching over the rolling hills south of Sharpsburg and into the jaws of battle, Oliver Case fully understood that he faced his own morality. He had been here before and he knew the danger…

There is not the dread of Death here as there; but I expect like everyone else to come out alive. I have yet to see the man that did not. It is much the best way on the men to go into action with high hopes and good spirits instead of feeling low and depressed.[2]

Oliver had witnessed the sting of death first-hand. He had seen his friends and fellow soldiers killed in battle. He stood with them as they fought horrible disease to the point of death. Death was familiar to Oliver, but death was not his friend…it was his foe as much as any Confederate soldier he might face. Meeting death was the encounter Private Oliver Case wanted to avoid, but knew that, sooner or later, he would face this enemy and death would come calling for the young soldier from Simsbury, Connecticut. For the Civil War soldier death was part of life and it could not be avoided.

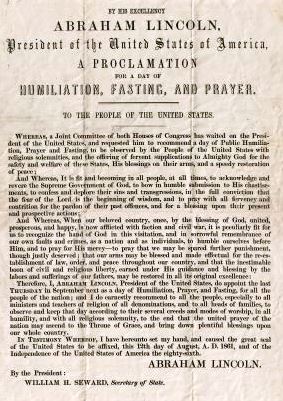

For himself, Oliver Case had resolved long before this mid-September day that he would not run in the face of his own death because a far worse fate would await him. As a witness to the dishonorable behavior of others as death began to stalk them, he wanted no part of such conduct. As he had done before on the coast of North Carolina, he would not falter as the bullets began to fly in his direction. Oliver, rather than choose dishonor, would rely on the mercy of God to choose his fate. He would not face the judgments of a pitiless people who would surely sentence him to a lifetime of shame for cowardly bearing before the enemy. In his letters to his sister and brothers, Oliver had drawn this as a clear line of battle from which he would not retreat.

Make no mistake, fear of the unknown always hovered about him. Like the fever Oliver had struggled against for so many of the past months, fear would always return, unwelcomed and inescapable. Oliver must have realized that if fear was an inevitable visitor, then he must face it head on and chase it from his mind. It was analogous to leaping into the swiftly flowing Farmington River back in Connecticut and trying to fight upstream against the current. No, rather than struggle against it, Oliver knew that he must ride the strong current of his fear to go where he did not want. Strength came from those men on his left and right who faced the same fear of dying but men with whom Oliver trusted his life. Oliver knew that only his God held the destiny of his young life and that must be his comfort.

But thanks be to God what is our loss is his gain.[3]

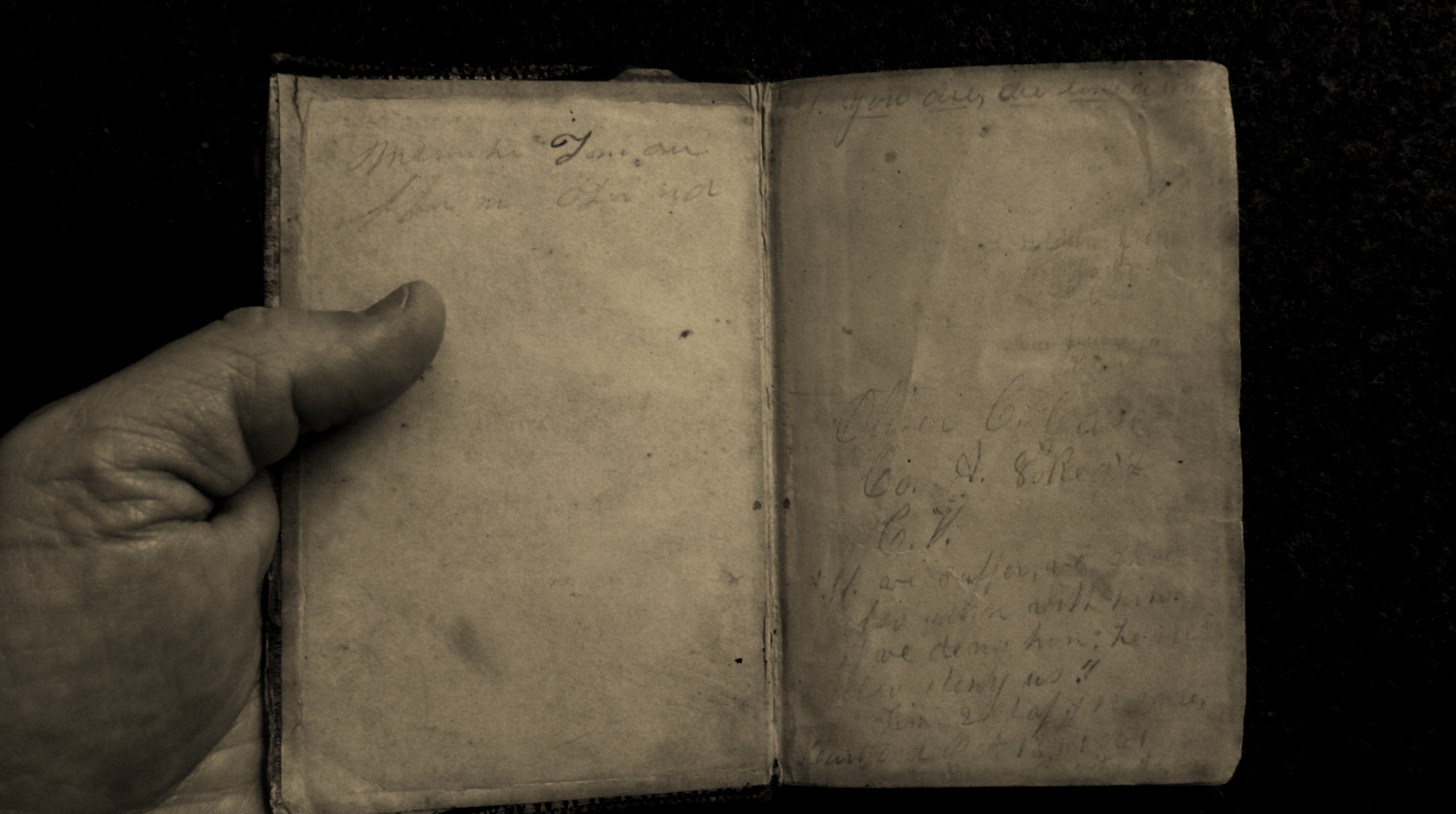

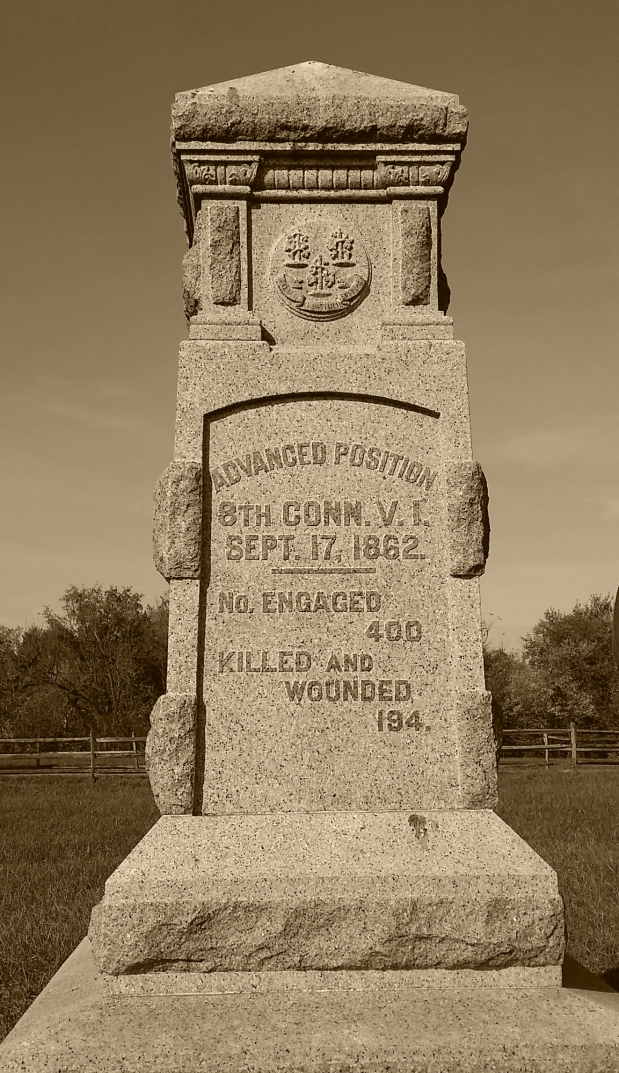

Late in the afternoon of September 17, 1862, the strength of honor bore up the hopes and spirits of Private Case and his fellow soldiers of the 8th Connecticut as the order was given to advance toward the Confederate lines outside Sharpsburg, Maryland. Their courage would now be sorely tested in these fields and across the rolling hills…[4]

How long can this continue? Over every one of these hills lies another storm of lead from those Johnnies. The boys are in fine fighting spirits today, so maybe just one more push over that next hill in front of us and then, we’ll make the Harper’s Ferry Road and the town of Sharpsburg. This will all be over if we can just make one more push. I can see two cannons of the enemy guarding the road at the top of that final hill. At least, I can see the business end of the guns as they begin to spew the deadly canister into our ranks. Artillery incoming! I want to bury my face in the earth. No, it’s ours…over our heads. Hitting all around the rebel cannons. There’s Captain Upham and his company moving up on our left; closing up quick on those guns. The smoke is clearing; rebels have abandoned their battery. Maybe we have a chance…we can win a great victory. The war will be over!

Wait…beyond those brave Confederate gunners, I can hear those officers in gray shouting at disoriented troops milling around the road. I hear the cries on the officers to “rally on the colors” and “stand your ground.” The sea of graybacks is swelling and the rebels in front of us are firing into our ranks or mostly above our heads. I’m sure glad this swale is protecting us from their Minnie balls. I see the Zouves to our right…those New York boys are firing hot but many are falling. Now they are beginning to slowly move back down the slope. Lieutenant Colonel Appelman is giving the order for the regiment to move forward followed by the echoes of the captains. Nobody hesitates; not one of us. All the boys are rising up all around me. Now I know how Philo Matson felt at Newbern. God forgive me for my ridicule of Philo because I now want to make myself missing from this field. Orton, Martin, Lucius…they jump to their feet…I must go with them. I will not leave them. I cannot disgrace my family. This may be my end, but I will not be branded a coward. God give me courage to face the enemy and, if needs be, my own death!

The field where the 8th Connecticut made their desperate stand just short of the Harpers Ferry Road

I haven’t seen the other Connecticut boys in the 16th since they stepped off into that big cornfield. Lots of firing coming from that direction. I can’t look back…Colonel Harland is urging us forward but he’s on foot and not riding his horse. What a fine officer and a brave man. More firing and a rebel yell rising from that cornfield Ariel and Alonzo marched into…God protect my brothers. What would our mother think if she knew all three of her boys were in the thick of the fight on the same field?

It seems like we’ve barely started to move when old Colonel Appelman falls to our front. Four men (I don’t recognize them) are bearing him rearward. There stands Chaplain Morris loading a rifle as the cartridge box dangles from his neck like he’s a common soldier. What is happening? Our position is desperate. The Major screams above the din for the regiment to lie down again. I must reload, aim, and fire. Only about ten rounds left in my box. What’s that on our left beyond the enemy battery now abandoned by Captain Upham and his men? Soldiers in blue? But, wait…a flag. The colors are red, white and blue, but not the national colors. I know that flag. I remember it from Roanoke Island. It’s a North Carolina regiment and here comes another one behind them forming into a double file. God help us, we are done for.

The bullets are hitting our ranks thick as flies now from our front and the left. It’s bad for our boys. Thud…Orton is hit on my right and crumbles to the ground. I’m kneeling and reloading but Lucius stands to fire in front of me…he shouldn’t. Too late, he’s shot twice in the chest spinning around and falling at my feet…his eyes wide open toward the sky. This is the moment I knew would come. No turning back…if I die, I die like a man. I stand, aim at the rebel color bearer, squeeze the trigger…darkness, silence…

The dread of death is no more for Oliver Case…he has finally met death, but on his terms.

I went with my Brother to the Eighth Regiment to learn the fate of my younger Brother Oliver and found only eight or 10 of his company left from about 40 they had in the morning. Was told by a comrade that stood beside him that he fell and he called him by name but no reply. Said he was no doubt killed. The next morning we were marched down near the bridge and lay there all day. No one was allowed on the field as it was held by sharpshooters on both sides. The next day September 19 myself and brother had permission to go over the field and look for our brothers body being very sure he was dead we each took our canteens filled with water and commenced that awful sickening tramp and if I could picture to you the sad sites that we beheld. The ground for acres and miles in length were strewn with dead and wounded. The wounded crying for water they having lain there the whole day before and two nights — but everyone was looking for some comrade of their own Regiment but some time that afternoon we found the body of our brother we were looking after. He was no doubt killed instantly the bullet having passed through his head just about the top of his ears. We wrapped him in my blanket and carried him to the spot where the 16th dead were to be buried having first got permission from the Colonel of the Eighth and the 16th to do so. The 16th men were buried side by side in a trench and they dug a grave about 6 [feet] from them and we deposited the remains of my brother and that having first pinned a paper with his name and age on the inside of the blanket. Then they put up boards to teach with name and Regiment on them. His body lay there until December when father went there and brought the body to Simsbury where it now lies to mingle with the soil of his native town.[5]

[1] King James Bible, 1 Corinthians Chapter 15, verse 55

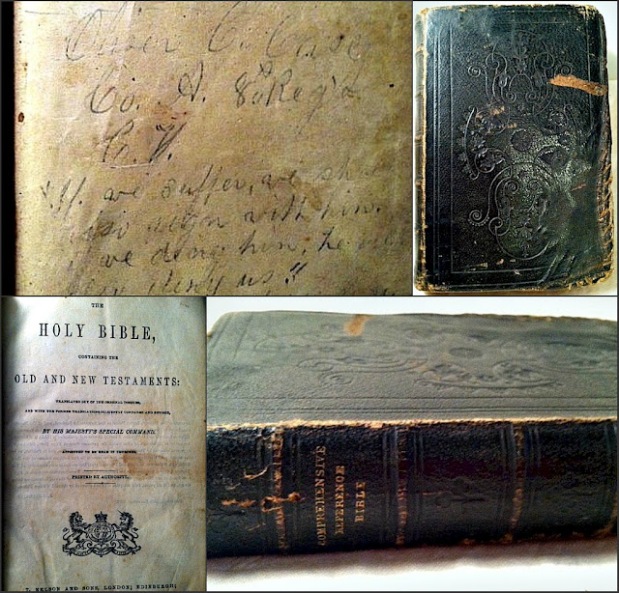

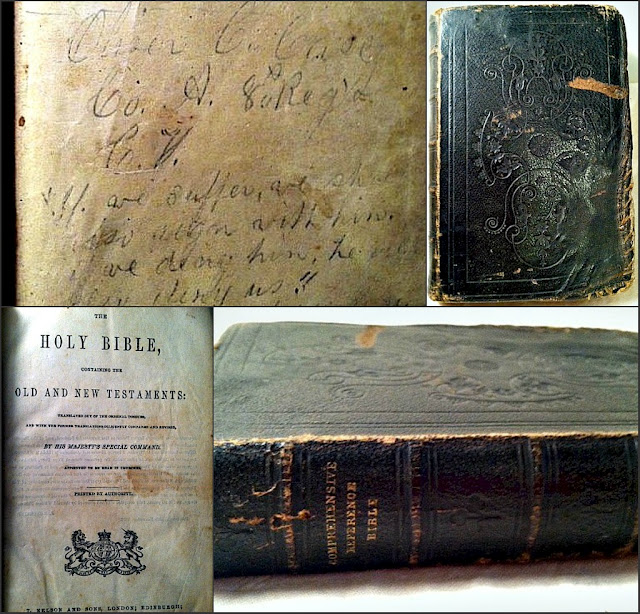

[2] The Letters of Oliver Cromwell Case (Unpublished), Simsbury Historical Society, Simsbury, Connecticut. While his was written regarding the coming battle(s) in North Carolina, the witnesses to his conduct on September 17, 1862 indicate that he continued to face the enemy and perform his duty as a soldier.

[3] IBID. In his letter of January 7, 1862, Oliver wrote these words in describing the death of his friend, Henry D. Sexton aboard a hospital ship in Annapolis harbor.

[4] What follows is a fictionalized account from the perspective of Private Oliver Cromwell Case using actual sources that describe this segment of the battle of Antietam and Oliver’s letters.

[5] “Recollections of Camp and Prison Life” by Alonzo Grove Case (unpublished), Company E, 16th Regiment Connecticut Volunteers (from the collection of The Simsbury Historical Society).