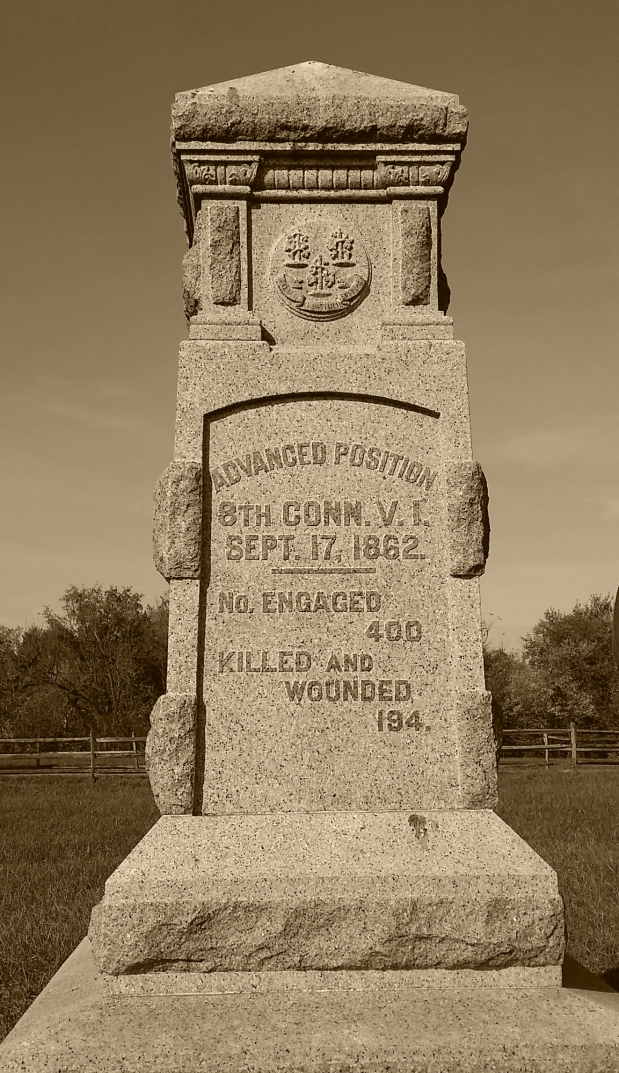

Private Oliver Cromwell Case was no stranger to the fight against disease. During his travels with the 8th Connecticut Volunteer Infantry Regiment to Long Island and then to Annapolis, Case struggled with Ague, an illness defined as “malarial or intermittent fever; characterized by paroxysms consisting of chill, fever, and sweating, at regularly recurring times…” and that can also be accompanied by “trembling or shuddering.”[1] Oliver found himself in and out of the hospital or confined to his tent with this condition also known as “chill fever” or “the shakes” in the popular vernacular. One surgeon of another regiment described effects of this condition for which he had no medicine by saying that his soldiers “have to shake it out for all the good we can do them.”[2]

Of the 360, 000 plus Union causalities in the Civil War, over 250,000 of those soldiers died from disease and other non-battle injuries while only about 110,000 died of combat injuries. Half of those deaths were caused by typhoid fever, diarrhea and other intestinal disorders with tuberculosis and pneumonia deaths following closely behind. Surgeons and commanders knew little about disease and the germ theory had not yet been discovered. Most of these young men had never been exposed to large populations living in close quarters that were often in filthy condition. Communicable disease outbreaks in the camps were commonplace.

Civil War soldiers line up for treatment of Ague[3]

As the New Year 1862 began, Oliver Case again faced a battle with disease but this time it was fought by two of his closest friends in the regiment. As evidenced by his letters, one of these two experiences with the monster of disease was likely his most impactful of the war outside of the combat at Antietam. In his letter of January 7, 1862, he describes it as “the most sorrowful time that I ever witnessed.” Henry D. Sexton and Duane Brown may have been pre-war friends of Oliver Case and his brothers but by the end of 1861, they had certainly become two of his closest friends. Oliver’s first mention of the two soldiers is in a letter to his sister on November 28, 1861:

I wrote to Ariel that Duane Brown and H.D. Sexton were sick at the hospital. I went to see them as soon as I heard of it, but could not get in where they were, but I looked in and saw their hall. I talked with one of Sexton’s friends who told me he was much better and expected to be around before long. The next day I succeeded in getting in where they were for a few moments. Brown is getting better also. Sexton was asleep. I heard from them Friday and presume by this time they are around. I should go to see them everyday…[4]

In Oliver’s letter of December 16, 1861, both Sexton and Brown seem to have recovered and sent respects to the Case family through Oliver. By the next mention of Brown and Sexton on the 30th of December, the situation changed significantly for both soldiers. Oliver, continuing to convalesce from his most recent outbreak of Ague, boards the hospital ship preparing to transport the sick to the North Carolina coast with the rest of Burnside’s expeditionary force. According to Oliver, Sexton’s “jaundice…is much better” but he is also loaded aboard the hospital ship in Annapolis harbor to continue his recovery.

For Oliver’s friend Duane Brown, the report of his illness is not good. Oliver writes to his sister, Abbie, that Brown’s condition did not improve after his most recent discharge from the camp hospital. However, Duane Brown possesses a distrust of the doctor and the medicine prescribed to him because “he thought the Dr. would surely kill him.”[5] Finally, Oliver and his friends convince Brown to go to “Surgeon’s Call” so that the doctor can evaluate his condition:

…the Doctor questioned him very close and told him he had better go to the hospital. I saw him a few hours afterwards and he was broken out very thick with the measles. He has had a very bad cough ever since he was discharged before and it has gradually increased to such an extent that it was almost impossible to sleep where he was. He would raise nearly a quart of phlegm a day. He has kept nothing upon his stomach for some days and the medicine he got at the Dr, we could rarely make take. He would sit bent over the stove day after day not willing to take any medicine and complaining continually of the cold.[6]

Duane Brown is hit by a double attack of disease. Not only is he suffering from “consumption” the Civil War era term for tuberculosis, now he is one of the first cases in Company A of the 8th Connecticut for an outbreak of measles in the camp. Oliver’s assessment of Duane’s condition is not bright:

I am afraid it will be a hard case. I have stated it just as it is and if you see any of his folks tell them just what you think best.[7]

It is notable that Oliver believes the desire or motivation to get well again is a significant factor in one’s ability to recovery from a disease. His observation of Brown’s behavior in the days following his discharge from the hospital lead Oliver to note that if Brown had “any ambition he would get well, or in fact would not be in the hospital now.”[8]

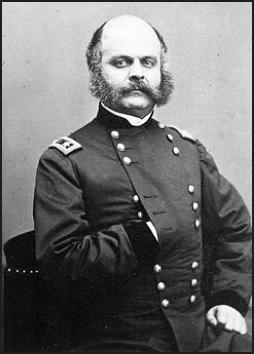

Meanwhile, the young soldiers’ commander, Major General Burnside is highly mission focused as the New Year begins. His purpose is to move as many troops as possible to the North Carolina coast to begin amphibious operations against the Confederates. Only those soldiers who have a good prognosis for full recovery within a few weeks are loaded onto the hospital ship. Among those men are Oliver Case and Henry Sexton. Both the assessment of the camp doctors and Oliver’s layman observation about Duane Brown seem correct as he is among those “those liable to be sick some time” who are sent “to the general hospital” in Annapolis.[9]

Oliver’s notation in his letter of January 7, 1862 seems almost cold and impersonal:

Duane Brown died and was buried yesterday.

But Oliver’s shortness is understandable as he stands in the midst of another battle with a friend. Later, in his letter to Abbie, he elaborates on Brown’s demise:

Duane went to the hospital Sunday with the measles and the Typhus Fever set it, and carried him off. He had the best of care at the hospital, as good or better than he could have had at home. Everyone that has been there speaks of the excellent care, accommodations, food etc. that they get there.

The good care of the hospital at Annapolis is too little, too late to save the longsuffering Private Duane Brown of the 8th Connecticut. Brown succumbs to the effects of disease on January 5, 1862. For his part, Oliver Case has little time to mourn the loss of his friend. Weeks later, Duane Brown will return to his mind as Oliver asks his sister, “How do Mr. Brown’s people take Duane’s death?”

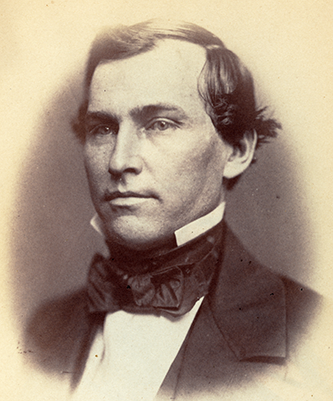

On January 7th of this new year, Oliver is fighting to save his other friend, Henry Sexton. Sexton, a former school teacher from Canton, Connecticut had enlisted for service on the 9th of September 1861 then married another teacher from Canton, Eliza Barbour, only ten days later. The pre-war connection of the Case family with Sexton is unclear but based on the tone of Oliver’s letters, his two older brothers, Ariel and Alonzo, were friends with Henry.

Sexton suffers from the effects of a condition that Oliver refers to as “jaundice.” During the war, Union armies would suffer more than 71,691 reported cases of jaundice likely a manifestation of hepatitis.[10] Alonzo Case obviously suffered from a similar condition because Oliveer describes Henry as looking “much as I have seen Alonzo.” Sexton came aboard the hospital ship Recruit along with Oliver on the 29th of December indicating his prospects for recovery seemed hopeful. However, Sexton’s health began to take a turn for the worse within a few days prompting Oliver to tell his sister that Henry “is on board quite sick with the jaundice…I do not believe he will go with us” on January 3, 1862.[11]

The life and death struggle of Henry Sexton would continue for four more days reaching its crescendo around noon on January 7th. Oliver’s multipart letter of the same date provides great detail of his journey for the past three days as Sexton’s condition rapidly declined into unconsciousness, wild spasms, and, finally, to a peaceful death. I think it best to let Oliver recount the story as he did for Abbie:[12]

Since I last wrote you I have seen the most sorrowful time that I ever witnessed. Henry D. Sexton died this noon of jaundice. He came on board the boat the same time I did and bunked under me until day before yesterday.

Sexton was a little worse Sunday, but not so bad, that he was around. He said that if he were at home he should be sitting in the rocking chair writing but as there was no place to sit down he kept his bunk. I prevailed upon the Dr. to have his bunk changed to a more comfortable one Sunday night and Monday morning I talked with him. I thought that his mind wandered a little. I left him about two. In the morning he was not conscious and repaired nearly all day in the stupid state. About three he had a spasm and rushed out of his bunk. I had no control of him as he could handle me like a child.

The spasm made Henry Sexton into a wild man causing him to lose control of himself.

It was very difficult to get anyone to take hold of him as they seemed to be afraid of him. It took five of us to hold him and keep him from tearing his face with his hands. He would bite at us and froth to the mouth, making a horrid noise all of the time. I stayed over him twenty four hours in succession before his death. I never saw anything so horrible in my life and if it had not been for the sailors I do not know what I should have done. He never has had any care upon the boat from the Dr.

Oliver is appalled by the lack of medical care from the doctor on the ship even after repeated pleas to help.

He [doctor] used to come around in the morning and ask him how he did – tell him to cover up and keep warm – perhaps give him a pill. He had only his own blanket and lay down upon the lower deck where it was very cold, damp, and close and where it was an impossibility to keep warm. I used to give him my blanket when I was on guard and when he could not get warm got into the berth with him. I tried all I could to have the Dr. convey him to the hospital Sunday when I began to see that he was getting worse. He also begged him to be carried there and he finally promised that he might go the next day, but the next day was too late. With even ordinary care he might have got well in a short time.

Henry Sexton’s melee with death has a profound impact on Oliver as he writes that he “never saw anything so horrible in my life.” Oliver continues:

I never felt so bad in my life as when I saw that here was no hopes of his recovery. It seemed as though I had lost the only friend I had with me.

The trauma of Henry’s death struggle coupled with the death of his other friend, Duane Brown, just two days before Sexton’s passing brought Oliver to a dark place where he felt completely alone. However, in spite of the painful experience with the deaths of his two friends, Oliver finds himself at peace with the passing of Henry Sexton:

Sexton died easy but unconscious…thanks be to God what is our loss is his gain. He was prepared for the final change. Only the day before he was taken unconscious he remarked that there was only one thing that supported him during his illness at the hospital, and now when he got low-spirited, “The religion of Jesus Christ was his sustainer.”

Physically and emotionally spent, Oliver is unable to write a letter to Henry’s wife informing her of the circumstances of her husband’s death relegating the task to a fellow soldier. In a letter to his sister, Oliver writes that he could not compose the letter so “I got another man to write to Sexton’s wife…” However, Case quickly adds that he “telegraphed this morning” presumably to Mrs. Sexton.

Eliza Naomi Barbour, Henry’s new wife, received the news of his illness in early January 1862 and departing Connecticut for Annapolis immediately. However, before she could reach Annapolis, Sexton died and was hastily buried likely due to the imminent departure of Burnside’s expedition. According to some local Annapolis historians, an area along West Street just outside of the downtown district was a possible temporary burial ground for the Union soldiers who died while Burnside encamped in the city. Today, no visible trace remains of any burial sites in this place. This location pre-dated the national cemetery later established further west of downtown. Due to the speedy exodus of Burnside’s forces, the temporary gravesites and remains may not have been marked to facilitate later removal and identification.

Modern-day Annapolis Visitor Center – Temporary burial site for Union soldiers was likely just west of this location

From the record of Oliver’s letters, it appears that Oliver was not present when Mrs. Sexton arrived in Annapolis or was not allowed to leave the ship. Although Oliver had telegraphed her soon after his death, it is likely that when Eliza Sexton came to the capital city of Maryland in search of her husband’s remains, it would have been a daunting task. With the departure of Burnside’s expedition only days before, the Union military presence in the city was greatly reduced and very little official assistance would have been available to Mrs. Sexton. When Mrs. Sexton arrived in Annapolis, the grave of her husband was not able to be located and she returned to Connecticut brokenhearted.[13]

Henry Sexton’s unidentified remains may have been relocated to the new national cemetery at a later date.

Annapolis National Cemetery: Could Henry Sexton’s unidentified remains rest here?

Henry’s wife and family would remember him through two memorials in the Canton Center Cemetery back in Connecticut.

Henry Sexton’s memorial marker in the Canton Center Cemetery.

Courtesy of John Banks Civil War Blog.

Henry Sexton is memorialized on his wife’s marker in the Canton Center Cemetery.

Courtesy of John Banks Civil War Blog.

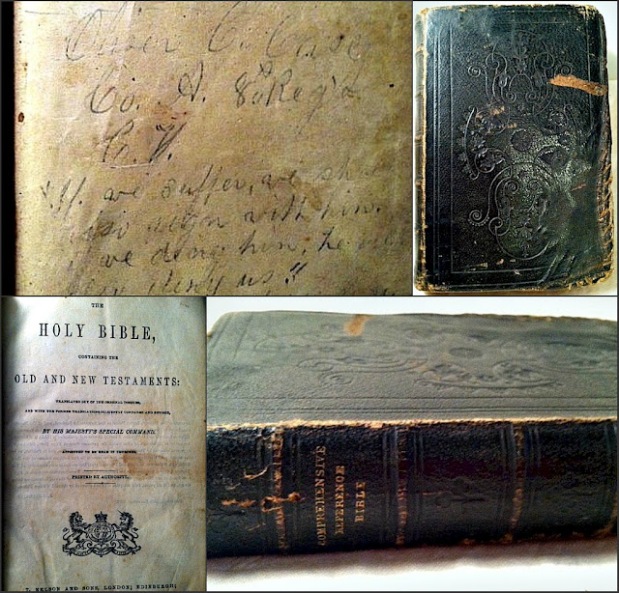

Oliver Case sought to bring the saga to a close by returning Henry’s possessions to his home:

We put all of Henry’s things in a box and sent by express. They would not let me help pay the expenses because they said that I had done my part by being with him all the time.

The events of the first week of January 1862 would follow Oliver for the remaining months of his young life. The deaths of Duane Brown and Henry Sexton would find mention in several of Oliver’s letters of the next few months as he could never forget the tragic loss of his friends to begin the new year of 1862.

ENDNOTES:

[1] “Rudy’s List of Archaic Medical Terms: A Glossary of Archaic Medical Terms, Diseases and Causes of Death,” accessed from http://www.antiquusmorbus.com/Index.htm

[2] A Surgeon’s Civil War: The Letters and Diary of Daniel M. Holt, M.D., Daniel M. Holt, Kent State University Press, 1994.

[3] Hardtack and Coffee, John D. Billings, John M. Smith and Company, Boston, 1887.

[4] The Letters of Oliver Cromwell Case (Unpublished), Simsbury Historical Society, Simsbury, CT, 1861-1862.

[5] IBID.

[6] IBID.

[7] IBID.

[8] IBID.

[9] IBID.

[10] Internal Medicine in Vietnam, Volume II, General Medicine and Infectious Diseases, Ognibene and Barrett, Office of the Surgeon General and Center of Military History United States Army, Washington, D.C., 1982, accessed from http://history.amedd.army.mil/booksdocs/vietnam/GenMedVN/ch18.html

[11] The Letters of Oliver Cromwell Case (Unpublished), Simsbury Historical Society, Simsbury, CT, 1861-1862.

[12] All the following quotes are from Oliver’s letter of January 7, 1862 unless otherwise noted.

[13] Reminiscences By Sylvester Barbour, A Native of Canton, Conn. and Fifty Years A Lawyer, Sylvester Barbour, 1908, Page 10